Water, Water Everywhere

But never where you need it.

Anonym

For some reason, water has been a big theme for me lately. Two weeks ago, it was a snow storm causing problems for a class I was teaching in Virginia and delaying my flight home to Colorado. Then I got a bunch of followup work for the arctic coastal erosion and bathymetric projects I’ve been working on. The Winter Olympics started, and brought the usual concerns about snow quantities. Now, I’m back in the DC area again this week to teach another class, and sure enough another snow storm is forecast to make a mess of roads and air traffic.

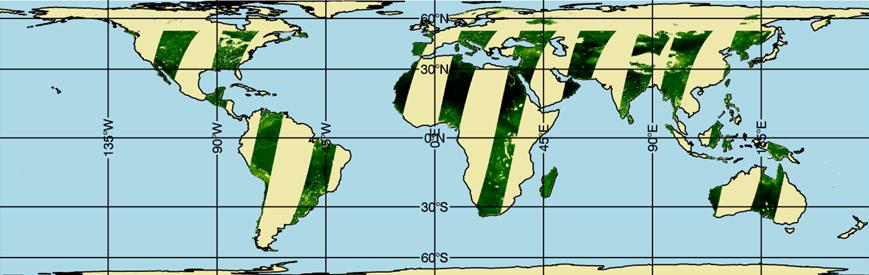

Precipitation, like most of nature, has a habit of following its own rules and systems which are at best loosely coupled to what we’d like to see. We get too much in some places, and not enough in others. But one project I get to work on in a small way promises to help us work with the water we have a lot more effectively. The first step in understanding an earth system is getting a decent map of it, and that’s not particularly easy. There have been some great earlier missions to develop and test the technology, like TRMM. The new missions, SMAP and GPM, however, will give us frequent global maps of where precipitation is falling, and where that water goes when it hits the ground. My little contribution is to make sure we can help get that data on screen in the ways scientists and end users want. When I get some more of the code finished, I’ll post it as a blog on making use of global data systems through HDF5 and map routines in IDL. But for now, here’s a sneak peek of where I’m at:

There aren’t many geospatial fields that don’t have a heavy dependency on precipitation and water. How will you use the new data from precipitation and soil moisture missions?